A tornado is an extreme meteorological phenomenon formed by a rapidly rotating, hollow, tubular airstream. It often takes the shape of a funnel, larger at the top and smaller at the bottom.

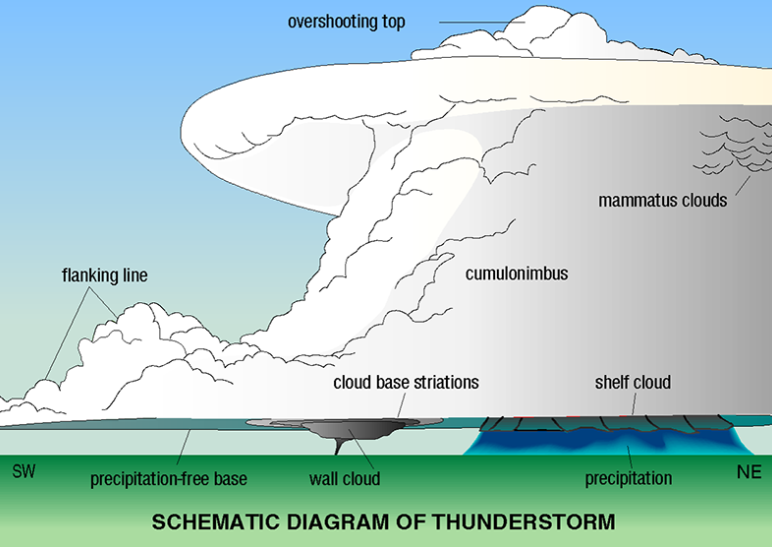

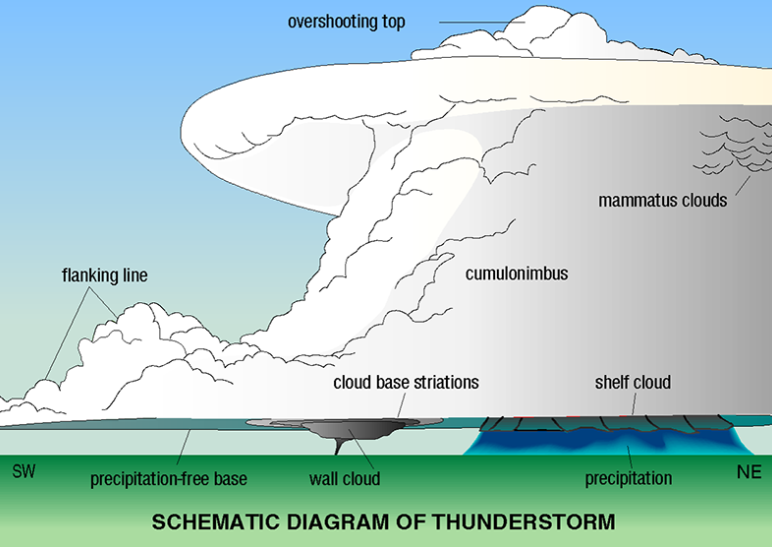

The upper portion of the funnel is connected to cumulonimbus clouds (or, in rare cases, cumulus clouds), while the lower portion is in contact with the ground and surrounded by dust and debris. Its formation requires three atmospheric conditions: an unstable stratification with warm, moist air in the lower layers and dry, cold air in the upper layers, sufficient moisture, and an uplift triggering mechanism. It is closely related to low pressure and shifting wind directions.

Forming Stages

Tornadoes often occur within unstable air masses characterized by high temperature and high humidity. The air there is extremely turbulent, resulting in a significant temperature difference between the upper and lower layers. While the temperature at ground level is around 30°C, it drops to -30°C at an altitude of 8,000 meters. This temperature difference causes the cold air to descend rapidly and the hot air to rise rapidly, resulting in rapid convection between the upper and lower layers, forming numerous small vortices. As these small vortices gradually expand and undergo violent turbulence, they can easily become larger vortices, causing wind damage that strikes the ground or the ocean. Tornadoes are the product of thunderstorms within clouds. Specifically, a tornado is a concentrated release of a small portion of a thunderstorm's immense energy over a very small area.

The formation of a tornado can be divided into four stages:

1. Atmospheric instability generates a strong updraft, which is further intensified by the influence of the largest air currents passing through the jet stream.

2. Interacting with winds that exhibit vertical shear in both speed and direction, the updraft begins to rotate in the central troposphere, forming a mesoscale cyclone.

3. As the mesoscale cyclone develops and stretches upward toward the ground, it thins and strengthens. Simultaneously, a small area of enhanced convergence—the, the nascent tornado—forms within the cyclone, forming the tornado's core.

4. The rotation within the tornado's core, unlike that within a cyclone, is intense enough to carry the tornado all the way to the ground. When the developing vortex reaches ground level, the surface pressure drops sharply, and the surface wind speed increases dramatically, forming a tornado. Tornadoes often occur during summer thunderstorms, especially in the afternoon and evening. Tornadoes have a small impact radius, typically ranging from a dozen to several hundred meters in diameter. Tornadoes typically last only a few minutes, or at most a few hours. Winds are extremely strong, reaching speeds of 100-200 meters per second near the center. Tornadoes are highly destructive, often uprooting trees, overturning vehicles, destroying buildings, and sometimes sucking people away, causing significant damage.

Meteorological Causes

From a meteorological perspective, tornadoes form when a large temperature difference between the upper and lower layers of a cloud creates a small vortex where cold air descends and hot air rises. This creates cotton-like white clouds called cumulus clouds. Cumulus clouds then develop within the larger vortex to form cumulonimbus clouds. The latent heat within the cumulonimbus clouds continues to increase, generating the powerful air currents that form the tornado. A tornado is a powerful and dangerous whirlwind that can occur over land (called a landspout) or over sea (called a waterspout). It occurs when a northward push of moist, hot tropical air is accompanied by the intrusion of cool, dry air high in the sky, creating a vortex that forms dense cumulonimbus clouds. As the vortex grows more intense, it can plummet from the clouds to the ground, forming a funnel-shaped column of cloud. Its strong winds create incredible destructive power, making it the most destructive of all atmospheric phenomena. A typical tornado travels at 55 kilometers per hour, but some have reached speeds of up to 115 kilometers per hour; the strongest tornadoes can reach speeds of up to 450 kilometers per hour. A typical tornado's lifespan ranges from 15 minutes to as long as 7 hours and 20 minutes. The longest recorded tornado was in Charleston, Mattoon, Illinois, in 1917, traveling 471 kilometers.